Desha–Kala–Patra in a Globalised World: What We Lose When We Forget the Wisdom of Place

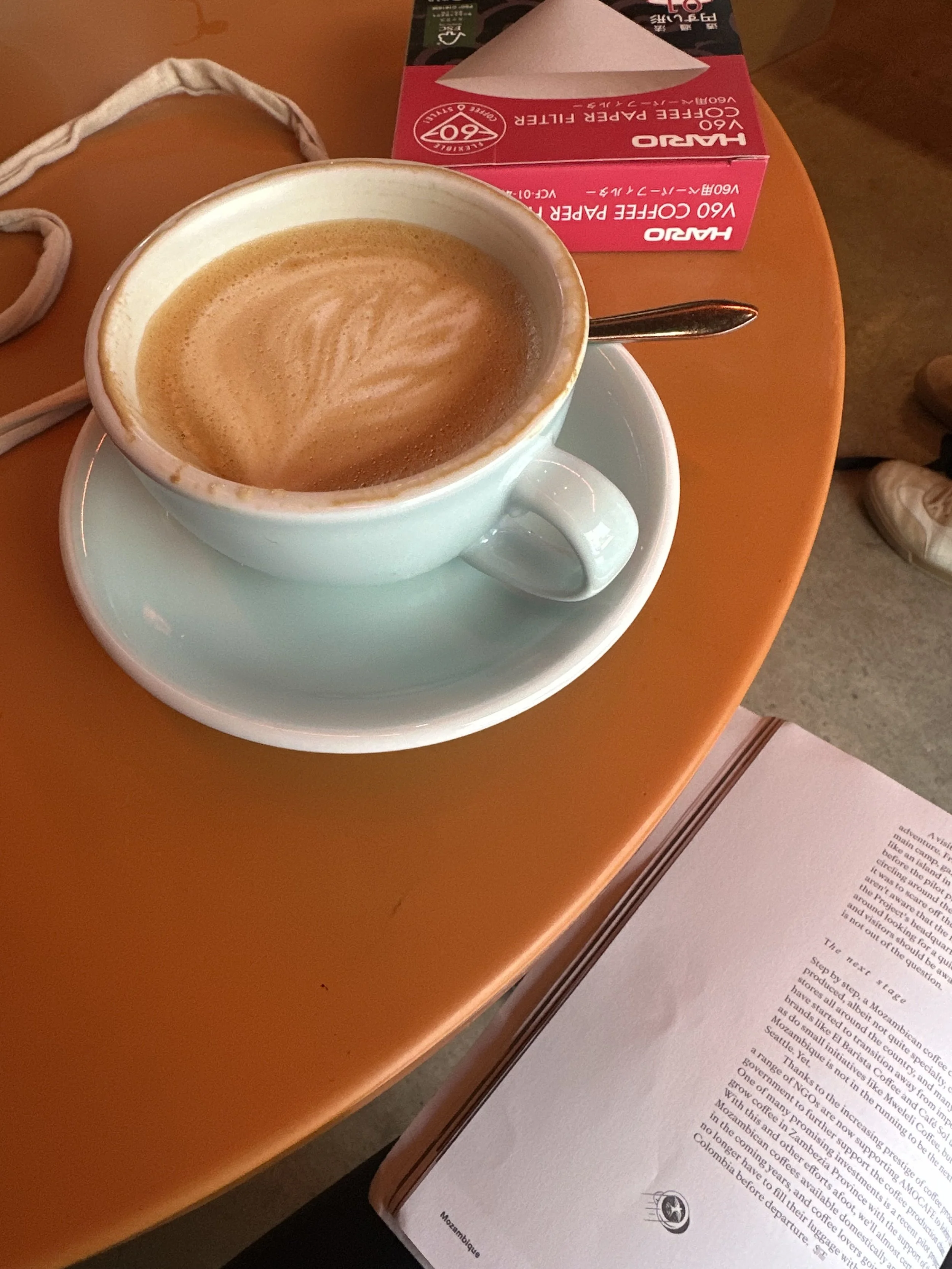

I was sitting at my favourite barista in Campo de Ourique, Lisbon, enjoying my occasional “after-gym celebration coffee.” I take mine with oat milk — mostly because dairy is discouraged in Ayurveda — and I limit myself to three coffees a week. But that’s another story.

That morning, as I sipped my cup, I came across an article describing how Mozambique is becoming a global front runner in high-end, eco-friendly, sustainable coffee production. From a tea nation to a coffee nation, all in the name of progress and economic advancement.

And suddenly a question rose in my mind: What does this kind of progress do to a nation in the long run?

I began thinking of other countries where similar transformations have taken place — nations drifting away from their origins, or sometimes exploiting them; places where traditional foods, drinks, rituals, and crops are slowly replaced by global trends. I wondered: What did each nation originally grow, drink, or eat — and why?

In today’s world, where everything is globally connected and accessible, it becomes easy to forget what grows naturally and organically in a place. Globalisation has given humanity incredible benefits: better access to nutrition, greater longevity, and the disappearance of many diseases caused by malnutrition. Yet countless communities still do not share in this abundance, and in some places, profits never reach the people who need them most.

There seems to be a delicate line between progress and tradition — a place where one can nourish the other, but also a place where one can overshadow or erase the other.

As I continued reading, my thoughts drifted toward the ancient Ayurvedic concept of Desha–Kala–Patra, and how, in classical India, this framework was not only applied to medicine but also to politics, economics, education, social structures, and community wellbeing. It guided decision-making in a way that honoured land, time, and people.

So I found myself asking: What happens when this wisdom is gradually detached from its land-time-vessel alignment and replaced by globalised habits, commodities, and stimulants?

And more importantly: If Ayurveda once stood in the margins of politics and economics, might it still hold a blueprint for decision-making today?

Would it allow nations to pursue progress without losing themselves — without harming the individuals and communities rooted in that land?

These are the thoughts currently forming in my mind, the beginning of a larger exploration, and I’m excited to share the unfolding of this reflection with you.

I am starting to express them with this “simple” example of Coffee. But this goes way deeper and further…..

In Ayurveda, every land has its own constitution — its Desha, its innate rhythm, its climate, its soil, its pulse. Time adds its own layer through Kala, shifting seasons, histories, migrations, and trends. And then comes Patra, the vessel: the individual, the community, the cultural body that absorbs or resists change. When these three fall out of alignment, the delicate thread of Oka Samya — the harmony between people, place, and life — begins to fray.

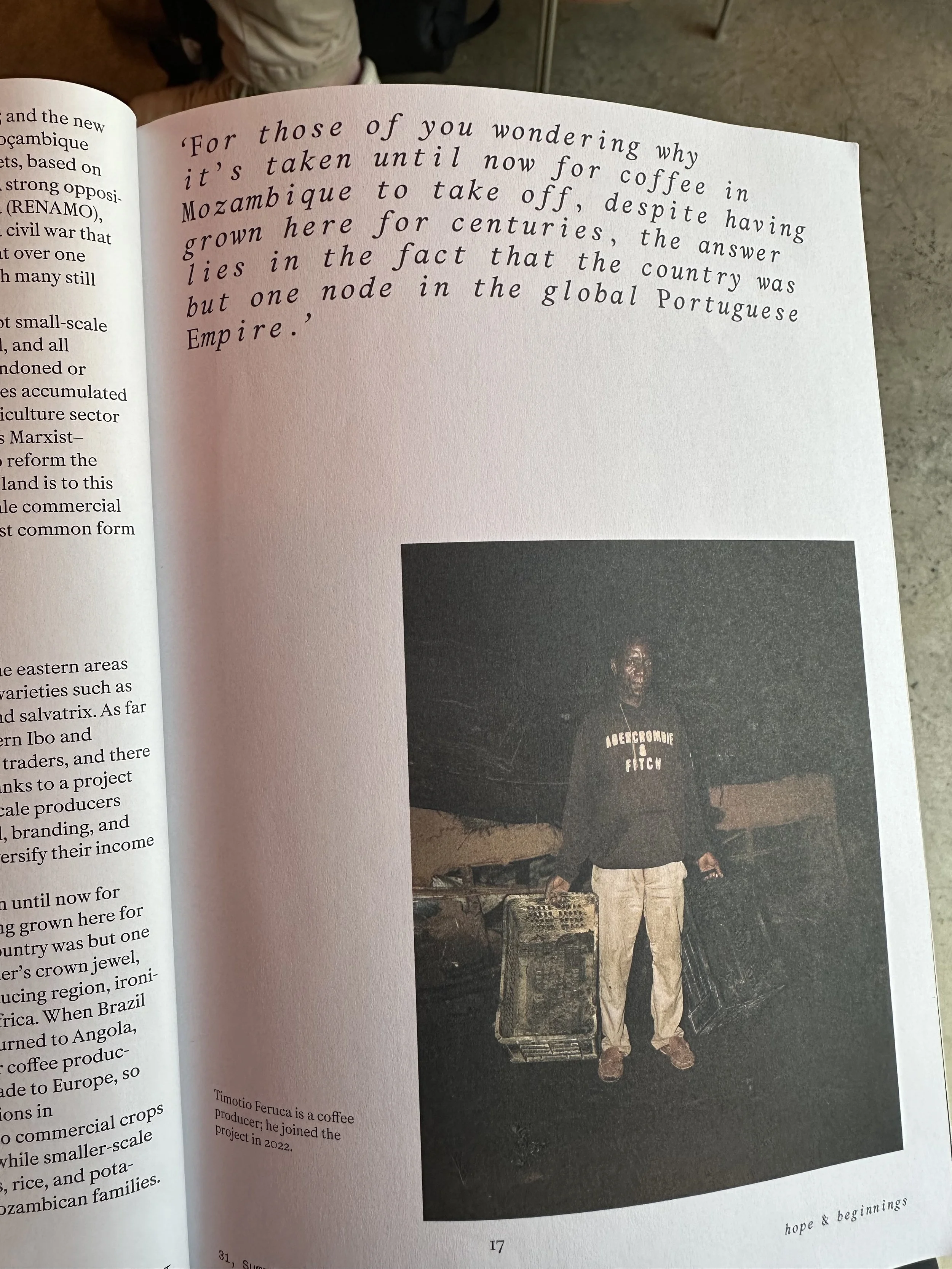

Mozambique offers a quiet but telling example. It has grown coffee for centuries, yet only now the world calls it a “coffee nation.” Long before it became an export commodity, coffee existed merely as a plant of the land — Coffea racemosa, a humble species that grew wild along coastal forests. Perhaps some communities roasted its small fruits, perhaps they brewed them on occasion, but the plant was not a defining feature of daily life. The rhythm of the land was shaped by another kind of drink: herbal teas, infusions of leaves, roots, and bark that rose naturally within a humid, warm, tropical Desha.

Such drinks matched the constitution of the place: cooling, hydrating, calming. They soothed the digestive fire without disturbing the balance of body or mind. They belonged to the coastline and its monsoon air, to the people whose skin and breath had adapted to the sea’s moisture. This slow intimacy between land and habit is precisely what Ayurveda calls Desha alignment — a relationship where consumption mirrors climate, and nourishment grows from familiarity.

But as Mozambique’s coffee industry grows and global trends drift in, one begins to wonder how the shift will unfold over time. Not all locals drink coffee today, yet the aroma has entered their mornings; the cafés multiply; the stimulant becomes part of the country’s imagined modern identity. And from an Ayurvedic perspective, this shift — gradual, cultural, energetic — carries implication. When a Kapha–Pitta land begins embracing an Ushna–Ruksha stimulant, the balance of the collective Desha can begin to tilt. Perhaps subtly at first. Perhaps only in cafés, workspaces, or cities. But over decades, a stimulant that was once foreign to the land’s natural rhythm can reshape not only the economy but the inner tone of a nation.

The irony is that the coffee plant itself tells a story of contradiction. In its raw form, coffee is bitter, astringent, and hot — qualities that, in classical herbal taxonomy, lean toward the toxic unless transformed. Caffeine sharpens, awakens, stimulates circulation, but also dries tissues and thins Ojas, the delicate essence of vitality. Through human craft — roasting, grinding, tempering with milk or spices — this fierce seed becomes manageable, even enjoyable. Ayurveda would call this a samskara: a refinement that reduces harmful effects. Yet even with all this alchemy, coffee remains a substance meant for moderation: ideally one small cup, early in the day, when Kapha is naturally high and sluggishness needs awakening. Beyond that, the same seed that sharpens clarity can quicken depletion.

This subtle friction between stimulation and sustainability is not unique to Mozambique. It is a sign of the global age — a time where the world follows a single rhythm of speed, caffeine, and convenience, often at odds with the natural intelligence of place. Every land once had its own medicine: Japan found serenity in matcha and the empty pause of ma; Ethiopia in its slow, grounding bunna ceremony; India in chai steeped with spice, warmth, and conversation; Mozambique in its wild coastal teas, prepared with leaves swaying alongside monsoon winds. Now that diversity flattens into a single flavour — the bitter, fast, stimulating taste of modernity.

Even matcha, once sacred to Japan’s humid mountains and contemplative Zen practices, becomes a global trend. But matcha is cooling, dry, and light — an ideal match for the heavy moisture of Japanese climate and the Sattvic temperament of quiet attention. In cold or dry regions, or in Vata-dominant bodies, excessive matcha can increase restlessness, dryness, and insomnia. What belongs to one land becomes disruptive in another. Ayurveda reminds us that medicine loses its wisdom when removed from the soil that shaped it.

Coffee too has its rightful place. For Kapha-dominant individuals living in cold, damp regions, a morning cup can kindle Agni, cut sluggishness, and move stagnation. During rainy seasons or after heavier meals, its bitterness supports elimination. The trouble begins when a Vata-Pitta person — already airy, light, or fiery — uses it daily for productivity, urgency, or emotional escape. Then, the same drink that suits one climate or constitution becomes depleting in another.

What connects all these observations is simple: context is everything. Desha–Kala–Patra is not a philosophy of restriction; it is a philosophy of alignment. When we forget the climate we live in, the time we inhabit, or the vessel we carry, our choices begin to override our inner intelligence. India illustrates this painfully. A country built on Yoga and Ayurveda — disciplines born from rhythm, slowness, and seasonal living — now leads global charts in diabetes and metabolic illness. The fast-food industry thrives in a land whose Desha once demanded warmth, simplicity, and gentle nourishment. When the land becomes hotter and drier, yet the people consume fiery, processed foods, the results speak through bodies, minds, and collective health.

Mozambique, then, stands at a threshold — not yet transformed, not yet imbalanced, but moving toward a global pattern whose consequences we have already seen elsewhere. If the land that once knew herbal stillness begins to hum with coffee’s restless pulse, its Desha may adapt, but it may also lose something subtle: the quiet alignment between land, habit, and inner balance.

Ayurveda does not ask nations or individuals to reject progress. Instead, it invites conscious adaptation — to honour the place we live in, the body we carry, and the time we move through. The question is never: Is coffee good or bad? Or more profound: Is PROGRESS good or bad.

The question is: Is this right for my Desha, my Kala, my Patra — today, in this season, in this land?

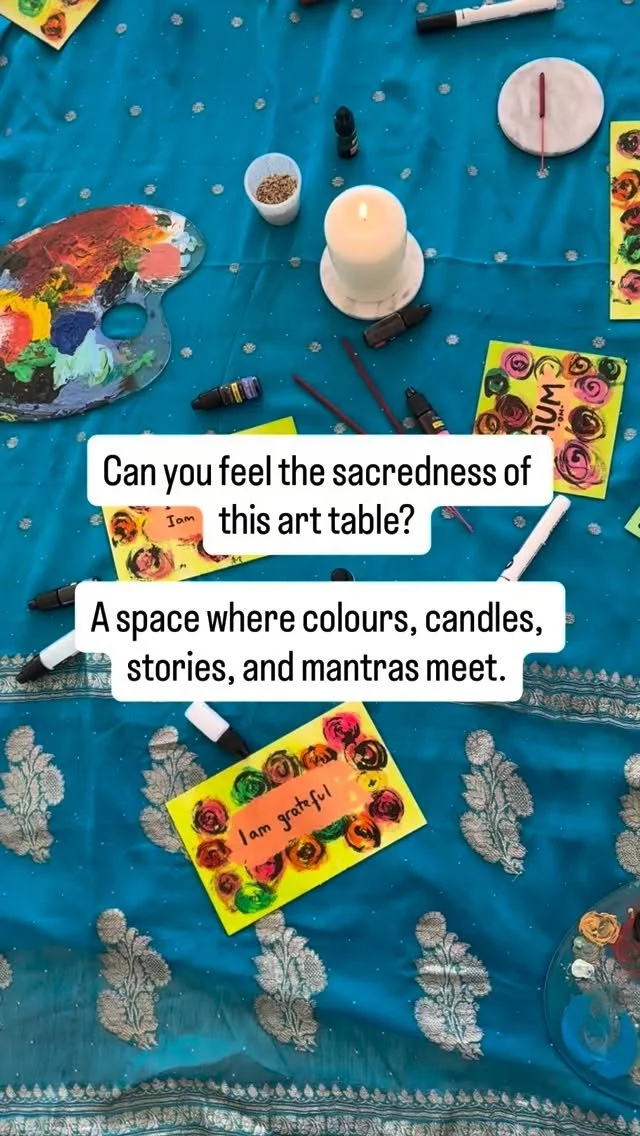

Perhaps the real revolution is not in choosing tea or coffee, but in remembering the rhythm beneath our feet. Because when a nation — or a person — forgets its constitution, it loses more than health; it loses identity. And when we remember Desha–Kala–Patra, balance stops being something we pursue. It becomes something that grows, like coffee once did, from the soil of the land we call home.

Thanks for reading.

Please share your thoughts with me and write me and reach out at mamta@soulveda.art

Follow me on Substack for the continuation of this thought process.

Mamta - Art & Ayurveda Therapist & Founder of Soul Veda