Krishna - the Playful Friend, Mentor and Reformer of Devotion

As a child, I often wondered if the gods looked like they did in the Indian series I watched—Krishna, Hanuman, the Mahabharata, Shiva, and the beautiful goddesses. I vividly remember sitting in a window seat on a plane, gazing at the clouds, imagining them seated on their grand thrones. Those shows were so popular that entire villages would gather around a tiny black-and-white TV. I joined these gatherings whenever I visited my grandparents in Punjab and Himachal Pradesh in the early ’90s.

Back then, I didn’t understand that the divine isn’t “out there,” but within us—able to manifest in many forms when we need it and allow it. In fact, this is the core principle of Hindu philosophy, upon which Yoga and Ayurveda are built: we are all divine because the divine dwells within us. I believe this is a beautiful and empowering message.

So, this month is once again dedicated to a different Indian deity and their mythology. We’re raising the bar, and this one is particularly rich and complex. But before we begin, here’s a quick recap of what we’ve covered so far this year:

Ganesha: The Remover of Inner Obstacles

Parvati: The Power of Devotion & Self-Discovery

Sarasvati: The Voice of Wisdom & Creativity

Rama: Dharma as an Inner Compass

The Month of August is all about Krishna - the divine friend, teacher, and guide

Krishna was born at the end of the Dvāpara Yuga, around 5,200 years ago (ca. 3200 BCE) according to Hindu chronology. When he departed the earth, the Kali Yuga began.

Understanding these cycles is essential to Hindu philosophy: time itself moves in great ages, or Mahayugas, each with a rise and fall of Dharma (virtue and purpose).

One Mahayuga = 4,320,000 years, divided into four Yugas. In each successive Yuga, Dharma diminishes by 25 %.

We are currently only about 2 % into the Kali Yuga—the “Dark Age,” where only compassion remains and spiritual practices simplify.

How do we know these dattes? Classical texts like the Sūrya Siddhānta fix the exact start of the Kali Yuga by recording planetary positions against the Julian day count.

From a narrative chronology standpoint, the Rāmāyaṇa comes first, followed by the Bhāgavata Purāṇa, and then the Mahābhārata. Interestingly, in terms of composition, the Rāmāyaṇa and the Bhagavad Gītā were written much earlier, while the Bhāgavata Purāṇas weren’t composed until roughly 800–1,000 years ago. This reversal reflects broader societal shifts and the growing emphasis on bhakti (devotion) over time.

Many of us ask: What is my deeper purpose?

In an age when spirituality can feel “out of reach,” Krishna’s life shows us that even in the Kali Yuga, we can reclaim Dharma through devotion, service, and inner transformation.

The stories

The Prophecy

Long before Krishna’s arrival in Mathurā, a divine prophecy set the stage for his birth. Mathurā—now in Uttar Pradesh, about a three-hour drive from Delhi—was ruled by King Ugrasena with fairness and righteousness.

Devakī’s marriage to Vasudeva was celebrated across the kingdom, watched proudly by her brother Kamsa. As he drove the newlyweds away in his chariot, the gods themselves mocked him, warning that he rode blindly into his own downfall: Devakī’s eighth son would slay him.

Devakī was regarded as an incarnation of Aditi, daughter of King Daksha and mother of Indra, the god of rain. In a past life, her sister Diti—spurred by jealousy—had cursed Aditi that all her children would perish before her eyes. Thus, from their very first pregnancy, Devakī’s fate was sealed.

Terrified, Kamsa imprisoned Devakī and Vasudeva and murdered each of their newborn sons. The parents’ grief soon grew unbearable, so he locked them in a dungeon. When Ugrasena—Devakī’s father and rightful king—intervened to plead for their release, Kamsa, blinded by fear and rage, deposed him and seized the throne. From that day on, paranoia consumed Kamsa, and he continued killing each infant Devakī bore.

Finally, on the eve of the seventh child, the goddess Yogamāyā (the power of illusion) intervened. She spirited the unborn child to Rohinī, Vasudeva’s other wife; that boy became Balarāma. Devakī, believing she had suffered a miscarriage, mourned deeply.

On the night of the eighth birth, Vishṇu appeared in Devakī’s dream. AS she tells him about her suffering, about the cruelty of Kamsa and how he has killed all her innocent babies, she beg Vishnoo to help her out of her misery, safe her 8th -yet unborn- child and then she becomes very specific: she requests Vishnoo to come to the earth in the shape of her son, and fulfill the prophecy and end the reign of Kamsa. Vishnoo can not say no unsee her suffering and promises to incarnate as her son - so this is when Vishnoo comes again to the earth disguised as Krishna. When Devakī slept clutching the newborn, Yogamāyā cast an illusion over the palace. Guided by that vision, Vasudeva slipped past the guards—put into a magical slumber—and carried the infant toward the Yamunā. As he stepped into the raging river, its waters parted into lotus petals and nāga-nymphs sheltered him from the storm.

Along the way, he reached the village of Gokula, home to Nanda and Yashodā: the humble yet prosperous leaders of the cowherd community. Nanda was beloved for his integrity and hard work; Yashodā, for her kindness and pure heart. Together they oversaw the herds with gentle care and open generosity.

At Nanda’s home, Vasudeva found a sleeping baby girl (Yogamāyā in disguise) beside Yashodā. He swapped the children and hurried back to Mathurā before dawn. There he placed the girl in Devakī’s arms and quietly withdrew.

When the illusion lifted, Kamsa rushed to execute the “male” child—but as he seized the infant, she revealed her true form as Yogamāyā. Proclaiming, “Your slayer has been born,” she vanished. In that moment, the prophecy was fulfilled: Krishna would live, and Kamsa’s reign of fear was doomed.

Putana - the demon that wants to become a mother: I forgive you, when you ask for forgiveness.

In Vrindavan lives the only-a-few-weeks-old Krishna, showered by endless motherly and fatherly love and already the center of the village’s attention and care.

The peace does not last long, however: Kamsa is determined to find Krishna. For this, he sends his most skilled and strongest warrior, the demoness Putana. Putana has a plan! She comes disguised as a beautiful, kind-looking maid and quickly wins the trust of Yashoda and Nanda. She says she has come from afar, having heard of their blessed parenthood, and wants to pay her respects and welcome Krishna by offering him her own milk and breastfeeding him. This was socially very acceptable in India at the time. It was fine for any woman who could breastfeed to feed another woman’s baby; it was considered a good deed and an honorable task.

Now there are two versions of the story:

In one, Putana actually develops motherly feelings for Krishna and cannot resist feeding him her milk, which is poisoned. She warns him beforehand and apologizes for it. Because her affection comes from the depths of her heart and is truly motherly, Krishna knowingly drinks the poisonous milk, and instead of killing her, he releases her soul and sets her free.

Krishna accepts every one of his devotees—even the “evil.” As long as, in their last moment, they devote themselves truly to him, he serves everyone. The relationship of give and take is strong here, too: as long as they offer their devotion, he responds with love and forgiveness.

Yashoda - The Devoted Mother: I bow to my mother, even if I am god.

In Vrindavan lives the only-a-few-weeks-old Krishna, beloved by all for his playful mischief. One day, as he played in the courtyard, Yashoda noticed him scooping handfuls of wet earth and popping them into his mouth. Alarmed, she rushed forward to snatch the soil from his fingers and scolded him: “What are you eating, child?!” To prove her point, she pressed her finger gently against his lips—only to taste dust. Furious, she gripped his chin and pried open his mouth, determined to punish him for his naughtiness.

But when Krishna opened his lips, Yashoda saw not soil, but the entire cosmos: galaxies, stars, oceans and mountains, unfolding in infinite expanses. In that instant, she glimpsed his true, divine form—and realized this was far beyond her understanding. Overwhelmed, she recoiled, tears in her eyes, feeling unworthy to behold such majesty. Swiftly, Krishna returned to his mortal guise, giggling like a mischievous child, and allowed Yashoda to hold him once more as her son. Relieved, she embraced him, her heart brimming with awe and renewed devotion.

Through this episode Krishna teaches a new mode of bhakti: rather than elevating devotees to the heavens, he descends to their level—inviting them to serve in the way they know best. He meets them in simple love, then reveals his divinity only as much as they can bear, so that their service remains tender and heartfelt.

These soul-stirring stories come from the later Bhāgavata Purāṇa and the Gīta Govinda, composed roughly 800–1,000 years ago. Though their events precede the Mahābhārata and the original Bhagavad Gītā in mythic time, these Purāṇic narratives were written centuries later, in a more relaxed, devotional age—transforming Hinduism’s earlier, more hierarchical vision into one of intimate, loving surrender.

The role of the Mother

I would like to focus on the role of the Mother.

In Hindu tradition, the Mother—both as divine principle and in her many earthly forms—embodies creation, protection, and unconditional love. At the cosmic level, she is Śakti, the living power that animates all things and bridges the infinite Supreme with our individual selves. She is at once nurturing and fiercely protective, guiding both material well-being and spiritual growth.

In the Purāṇas, we meet her in various forms:

Devī-Śakti, the primordial Mother-Power, source of all energy and life.

Pārvatī, the creative Mother who balances and renews the world.

Sītā, whose brave loyalty and resilience in the face of exile and hardship inspire unwavering devotion.

Kauśalyā, whose sacrifice and dignity illuminate a mother’s suffering and strength.

Śakuntalā, the single mother whose gentle compassion and courage shape her son’s destiny.

Kuntī, whose unbreakable will and fierce love sustain her sons through every trial.

Foster-mothers, too, are revered as living embodiments of this divine Mother:

Yashodhā, who nurtures and protects Krishna, her foster-son, with boundless tenderness.

Kuntī, again, who raises Nakula and Sahadeva as her own, exemplifying motherly devotion beyond biology.

Radha, whose all-encompassing love and steadfast loyalty toward Krishna echo the deepest maternal bond.

Across all these stories, one theme shines through: a mother’s love - In Hindi we have a word for this specific love: Mamta (yes, that’s my name too) —whether born of blood or of the heart—is a sacred force, a living thread of Śakti that upholds life, sustains virtue, and mirrors the divine.

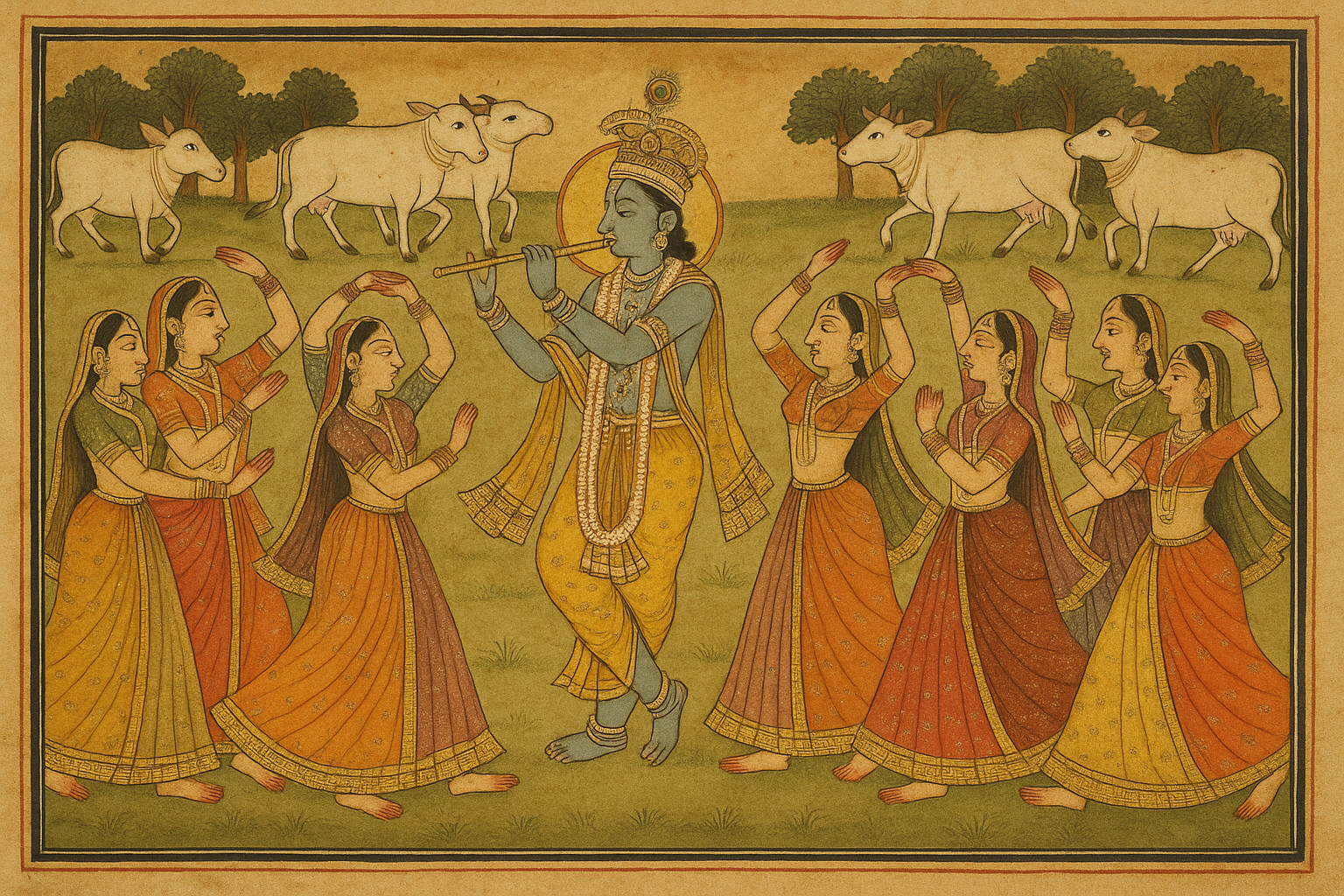

Radha & Krishna - The Raas Leela

Raas means the “juice of life.”

Leela means “play.”

It is a dance of trance, of love, of joy—where we forget everything around us and become one with ourselves, and through that, automatically one with the divine.

When Krishna grew older, he was no longer the innocent little boy. The mothers could no longer teach him—they had lovingly nurtured him, but he had outgrown them. Yet their love remained, though it transformed. This invites us to reconsider the definition of love.

What is love?

We tend to label love—to pin a tag on it:

Love between siblings

Love between parents and children

Love between lovers

Love between friends

Love between husband and wife

And much more…

But love is beyond labels. It does not require tags, nor is it bound by relationships alone. The Raas Leela embodies this: it makes us feel in love with everyone. It is unconditional, limitless, and without expectations. When we give love, we receive love—and that reciprocal flow is the only true response. This is the essence of the Raas Leela.

Radha exemplifies this devotion. She is the “chosen” one, the most daring—and perhaps the most erotic—but she also endured immense backlash for loving Krishna so deeply. In some traditions, Radha is said to be older than Krishna and never his wife, yet she harbored no resentment. She understood Krishna’s divine mission and continued to love him as he loved her, dancing the Raas Leela and spreading boundless devotion.

Socially, Radha’s role was not always acknowledged. She does not appear in all recensions of the Bhāgavata Purāṇa or the Gīta Govinda across every region of India. At times, her role as Krishna’s “beloved” was downplayed—perhaps deemed too erotic or too empowering. Yet the Raas Leela and the Radha–Krishna relationship ultimately empowered women, inviting them into devotional practices on equal footing with men. This marked another reformation in Hinduism, one that was not universally welcomed.

In a society where romantic love without parental approval is often frowned upon, the story of Radha and Krishna inspires young and old alike to dare to love, to choose their life partner, and to follow their heart—because the divine has shown them how, and that it is perfectly fine.

I remember perfectly a time when rather traditional families were trying to teach us, as young teenagers, that it was wrong to think about romantic relationships or choose our own life partners. They still hoped that my generation of Indians living abroad would opt for arranged marriages.(I want to make clear here, that this I am not against this concept. I have seenmany warm and loving relationships fruiting out of it. What is important is to always have the right of choice!) Especially as a young teenager I was often drawn to the stories of Radha and Krishna, and one day I confronted my parents with this question: How is it that society creates norms as it pleases, while altering the essence of what our gods and our religion have taught us? Radha and Krishna were never married, yet aren’t they the most iconic couple in Indian mythology, with Radha now honored in her own songs and temples? Why, then, are young girls in real life—and society—denied the chance to be modern Radhas too? This is the power of the reformation that Krishna brought to my life, empowering me as a young woman—and it’s the transformative power he continues to bring to many others today…

The fulfillment of the prophecy.

One day, Kamsa, having long since forgotten the prophecy, organized a bull-race in Mathura. There was a prize for the winner, and the victor would earn a personal audience with Kamsa himself. This presented the perfect chance for Krishna to return to Mathura. Why would Krishna want to go back for someone he did not know, especially while he lived in paradise? Well, let us not forget that Krishna is an avatar of Vishnu—and Vishnu had promised revenge to Devaki, Krishna’s birth-mother. Despite never having met her, he was bound to her by an invisible thread: he longed for her and felt her pain.

With the help of his brother Balarama, he set out for Mathura. Upon entering the city, Krishna immediately sensed the fear and suffering of its citizens; his urge to help grew even stronger. Winning the bull-race was an easy task for the brothers, and defeating Kamsa’s finest wrestlers and warriors felt like a raas-leela dance to them. Kamsa was intrigued but also insulted that his best-trained fighters had fallen to two village boys. At last, he summoned Krishna to his throne, and only then did he realize his grave mistake.

A fierce battle ensued, but even here, the playful power of the raas-leela overcame ego and physical might. With a single mighty punch, Krishna struck Kamsa down and freed Mathura from his tyrannical rule. The prophecy was fulfilled.

For the fulfillment of that prophecy, one theme stands out—one that resonates even with the many wars we see in the world today. A savior is truly a savior only when he frees others and restores dharma. Someone who has lived in captivity and war their whole life knows nothing but pain, suffering, and hatred. It takes time—and presence—to help cultivate love and peace again. That’s why we need teachers, guides, mentors, and peacemakers; you cannot simply fight fire with fire and expect it to vanish.

This lesson shines through in Krishna’s actions after he defeats Kamsa. Rather than immediately departing, he stays in Mathura, offering his counsel and support. He becomes the chief advisor and counselor to King Ugrasena, guiding him to restore stability and harmony to the city. This role of advisor is one Krishna carries for the rest of his life—most prominently during the events of the Mahābhārata—showing us that lasting peace is built not just by vanquishing injustice, but by nurturing hearts and societies back to health.

Krishna does not enforce his knowledge on anyone—he could, for he is God. But he understands that not everyone is capable of handling such great power. He knows there are different ways to help each person realize their own capabilities and to live in alignment with their dharma.

We will explore this further in the next session, when we discuss Krishna’s role during the Mahābhārata and his teachings in the Bhagavad Gītā.